Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain (the “ICTS Supply Chain Rules”)

The Department of Commerce leads the most advanced application to date of ownership tests for national security purposes. Foreign adversary nexus through offshore entities, special shares, proxies, dominant minorities, persons financed or subsidized, parties acting in concert, and persons subject to orders or requests are all targets under the ICTS Supply Chain Rules.

n Executive Order 13873, the President determined that foreign adversaries exploit vulnerabilities in U.S. information and communications technology and services (“ICTS”) to sabotage or subvert their integrity, including through integration with third party products and services. The Department of Commerce (“Commerce”) issued the ICTS Supply Chain Rules to address these national security risks by prohibiting certain technologies and services from reaching the United States. The ICTS Supply Chain Rules have a complex history and continue to evolve periodically to capture emerging technology and services.1

Commerce implements these rules by evaluating ICTS transactions to determine whether they meet the following three factors:

Each factor is discussed in further detail below.

In the event Commerce determines all three factors are met, it is empowered to issue an initial, and then final, determination to block all such transactions throughout the supply chain. This blocking power has far-reaching consequences due to the nature of how information technology is integrated throughout multiple layers of third-party products and services (e.g., “white labeling”). In this regard, Commerce may block: (a) updates to pre-existing software and other systems, (b) any operation of a product or service whatsoever in the U.S. or on any U.S. persons information system wherever located, (c) resale or integration into other products or services, and (d) licensing for purposes of resale or integration into other products or services. An ICTS final determination is akin to classifying a technology or service as a malicious computer virus. It must be removed from all systems and at every level of integration with other systems throughout the supply chain.

The ICTS Supply Chain Rules are quite sweeping in their scope. One way to think about their scope is to first consider indispensable consumer items, such as the Apple iPhone. In the event a Chinese supplier to Apple were to meet the three factors above, Commerce may block that supplier and require that each step of the supply chain be cleansed of the technology or services of that supplier which were so determined. Considering more complex supply chains involving all manner of U.S. technology infrastructure and industry, one can see the sweeping nature of these rules. (It should be noted that where CFIUS and the ICTS Supply Chain Rules overlap, CFIUS overrides.)

Is the transaction a Covered ICTS Transaction?

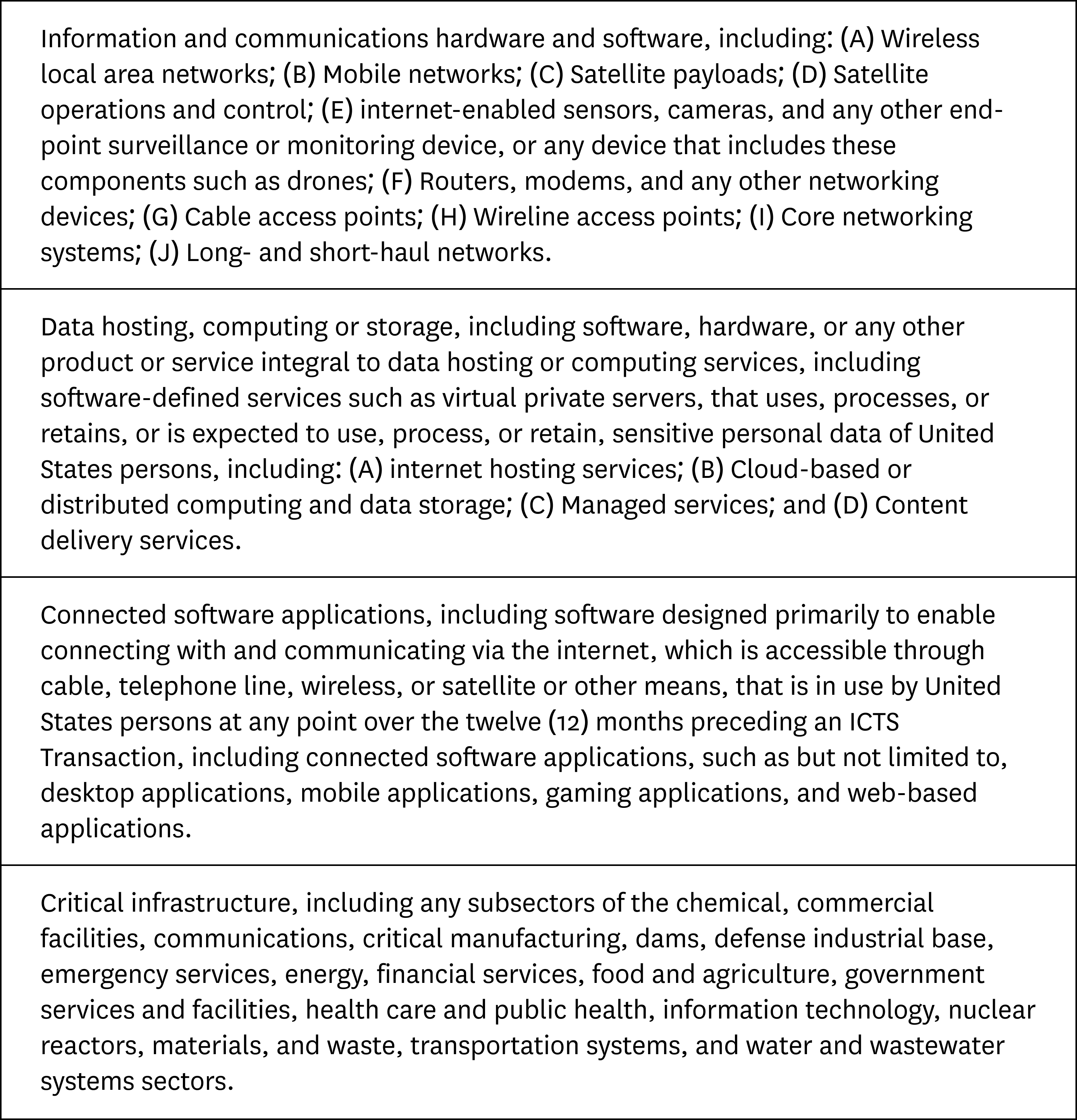

A Covered ICTS Transaction is defined in the following manner:

In addition to these categories, special rules exist for ICTS relating to connected vehicles. For example, there is a categorical prohibition for transactions meeting the Adversary Ownership Test for China or Russia that directly enable connected vehicle Automated Driving Systems or Vehicle Connectivity Systems.

.png)

Does the ICTS provider trip the Adversary Ownership Test?

The Adversary Ownership Test is tripped if the designer, developer, manufacturer, or supplier of a given ICTS is a person (i.e., individual or entity) owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of:

The Adversary Ownership Test is probably the most advanced national security style definition currently published. Following below is a discussion of its components, in order of increasing complexity.

All citizens and residents of foreign adversary countries are covered persons provided they are not also U.S. citizens or permanent residents of the United States. Commenters were concerned that this category of the Adversary Ownership Test would implicate U.S. entities and their foreign subsidiaries to the extent those entities employ foreign nationals. Commerce clarified that absent ownership, control, or influence by a foreign adversary, solely employing such individuals would not independently trigger an ICTS transaction review under this component of the Adversary Ownership Test.

All corporations, partnerships, associations, or other organizations with a principal place of business in, headquartered in, incorporated in, or otherwise organized under the laws of a foreign adversary are also covered persons. This category clearly includes U.S. companies’ non-U.S. subsidiaries or operations located in foreign adversary countries. Commerce expressly rejected requests to remove such entities from the scope of the Adversary Ownership Test during the comment period, indicating that they pose national security risks where the subsidiary might be required to comply with local country rules.

Offshore entities and U.S. entities can be covered under the Adversary Ownership Test in a variety of circumstances. First, all such entities, wherever located, that are subsidiaries of foreign adversary country entities or persons are covered persons. While the headline ownership threshold is stated to be those entities which are “owned or controlled”, this is considerably broadened (see discussion below). In addition, due to the use of the headquarters test, offshore entities (and potentially U.S. entities) could be covered based on facts and circumstances used to apply that test. See our prior discussion regarding how the headquarters test for national security purposes can apply to offshore entities such as the Cayman Islands.

Ownership at a threshold less than control is clearly contemplated under this component of the Adversary Ownership Test. This is because covered persons are specified to include the above persons (foreign adversary natural and legal persons) who possess the power, direct or indirect, whether or not exercised, through the ownership of a majority or a dominant minority of the total outstanding voting interest in an entity, board representation, proxy voting, a special share, contractual arrangements, formal or informal arrangements to act in concert, or other means, to determine, direct, or decide important matters affecting an entity.

A dominant minority could apply in a variety of situations such as to typical start-up companies and various types of sovereign wealth fund sponsored investments. For example, offshore companies used to structure start-up companies may have diversified financial investors, founding members, and the public (following a capital market event). Apart from the public, either group could constitute a dominant minority depending on the detailed structure. In the case of China, sovereign wealth or government guidance funds could as a group serve as a dominant minority. These funds may often serve as anchor investors in offshore investment funds that in turn could take dominant stakes in the portfolio companies beneath it. For example, the substantial overseas investment activities of China Investment Corporation (“CIC”) could implicate the application of the Adversary Ownership Test.

Certain board members with dual roles, such as active or former foreign government officials would presumably trigger this component of the Adversary Ownership Test. As discussed below regarding “persons acting at request,” a board composed of foreign nationals from an adversary country even if there is no specific risk tied to a given individual. Further guidance may be required to determine how this applies in situations where the board is fairly diversified.

The inclusion of special shares could be a direct reference to the Chinese pattern of using the special management share system (特殊管理股制度) to hold government interest in certain sensitive public and private companies. See our prior discussion on this type of share. Generally, the category would also cover various types of preference shares that grant rights not commensurate with the amount of shares owned.

Various types of proxy or agency arrangements (colloquially referred to at “代持” in China) would presumably be targeted with this addition to the Adversarial Ownership Test. Under such arrangements, a nominal shareholder (名义股东) holds on behalf of or for the benefit of the actual shareholder (实际股东). In addition, various types of Variable Interest Entity (“VIE”) arrangements would be covered. For a regulatory definition of VIEs, see our discussion in the context of the Reverse CFIUS rules.

It will be instructive to see the “acting in concert” standard applied, in particular, the type of evidence that may be required. Usually there would have to be some evidence of coordinated efforts or actions and/or shared objectives, plans, or designs. Given this and the above additions to the Adversary Ownership Test, it is clear that the trend is moving towards examining the substance of a relationship and not just the formal face of the agreements. Historical data and grouping of known individuals provided by WireScreen will be key for analyzing these types of issues.

Further beyond formal ownership, the ICTS Supply Chains rules also treat the following as covered persons:

The initial components of these rules would typically cover officers and employees of State-owned Enterprises (“SOEs”), not to mention per se government officials. However, a further step is taken for those acting at an order or request in the context of national security laws found in places like China and Russia.

As illustrated in the Kaspersky Labs case3, Commerce determined that any person subject to the jurisdiction of a foreign adversary must comply with any government request for assistance or information. These laws typically compel all persons to cooperate with intelligence and law enforcement (and Communist Party) efforts. In that case, it was specified that such abilities mean the foreign adversary can exploit access to sensitive information in the United States and even install or inject malicious tools into U.S. networks. Notably, this possibility was not disputed in the case even though there was no specific allegation of such exploitation at issue. Since these types of foreign national security rules attach to natural persons, all foreign nationals of an foreign adversary country could be suspect.

The introduction of persons financed or subsidized could cover a wide range of actors from those issuing debt to various types of donation recipients, cooperation projects, and other financial assistance. Further guidance would be needed to understand the extent of subsidization, for example in-kind types of benefits.

In regard to each of the above persons, the Adversary Ownership Test specifically includes them as a class of persons analyzed for purposes of the dominant minority, board representation, proxy voting, and others above.

Does the transaction fall under the National Security Risk Criteria?

The criteria used by Commerce to determine whether a transaction poses an undue or unacceptable risk is based on a broad library of USG threat assessments and reports, exclusion orders as well as statements and actions of the parties, the technology itself, and the nature of the transactions at issue. In the Kaspersky Labs case, Presidential Policy Directive (PPD) 21: Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience4 was used as the relevant risk criteria.

Some highlights for national security risk criteria analysis include the following:

In all cases, Commerce may consider “any other source or information deemed appropriate” and where national security criteria are not initially met “future review of the transaction shall not be precluded.”

1The ICTS Supply Chain Rules went through several iterations. The first version was issued on November 27, 2019 (84 FR 65316), followed by interim rules on January 19, 2021 (86 FR 4909), revisions on November 26, 2021 and June 16, 2023 (86 FR 67379 and 88 FR 393353), additions for connected vehicles on March 1, 2024 and September 26, 2024 (89 FR 15066 and 89 FR 78088), and final rules on December 6, 2024 (89 FR 96872)(codified as 15 CFR Part 791). Most recently, proposed additions for unmanned aircraft systems were issued on January 3, 2025 (90 FR 271).

2Property in which a foreign country or national thereof has any interest is interpreted broadly to mean an interest of any nature whatsoever, direct or indirect. See Holy Land Found. for Relief & Dev. v. Ashcroft, 333 F.3d 156 (D.C. Cir. 2003). The ICTS Supply Chain Rules further specify that this includes interest in contracts for the provision of technology or services.

3Final Determination: Case No. ICTS-2021-002, Kaspersky Labs, Inc., 89 FR 52434 (June 24, 2024).